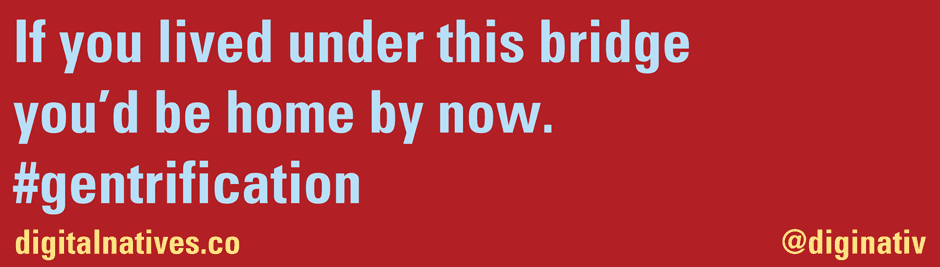

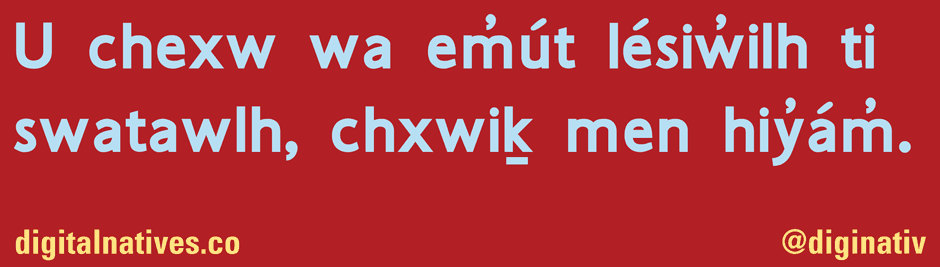

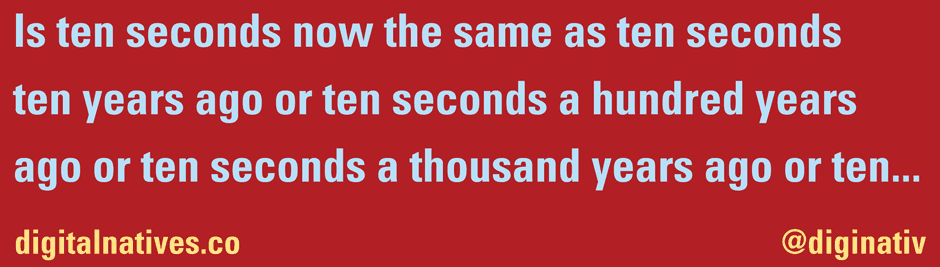

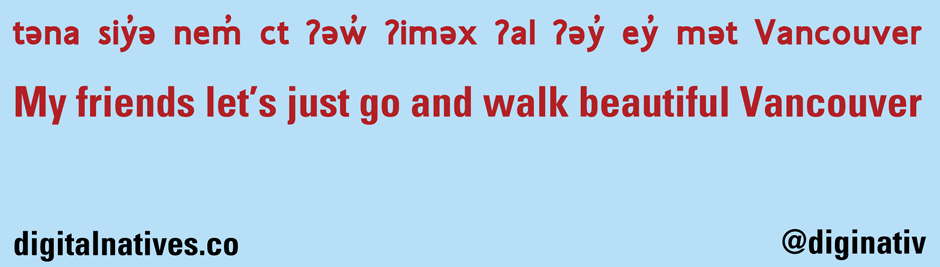

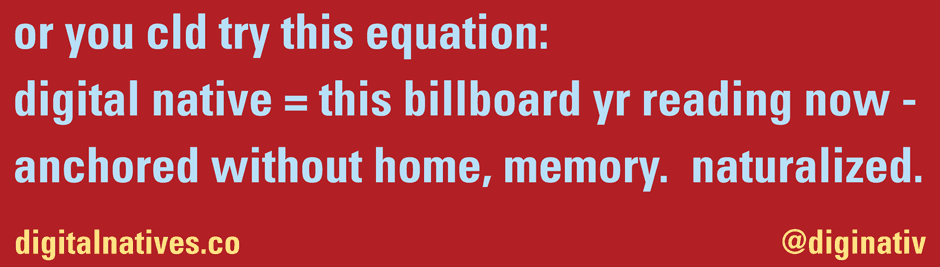

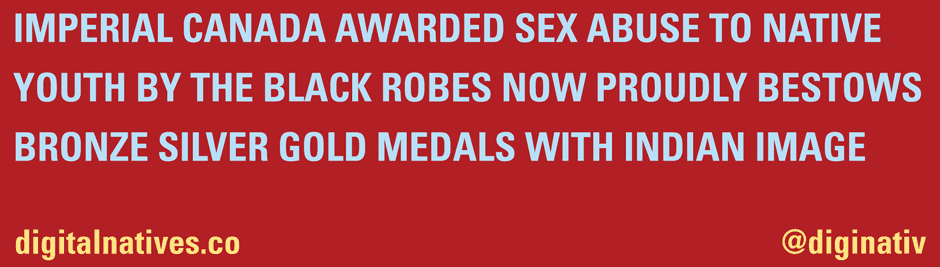

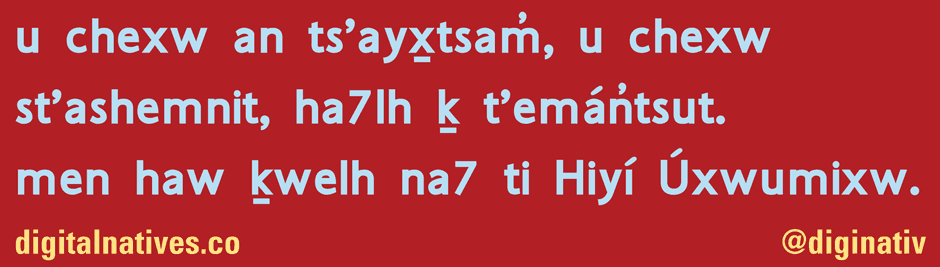

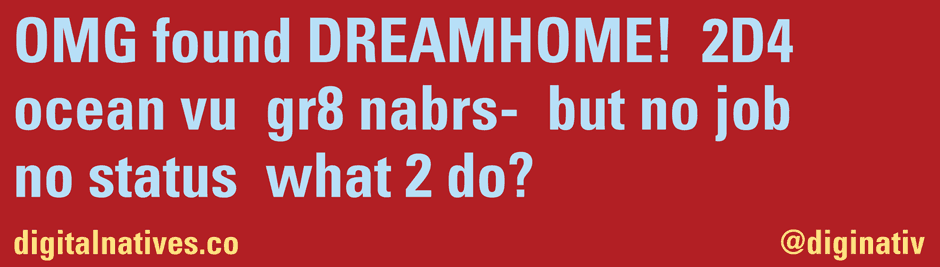

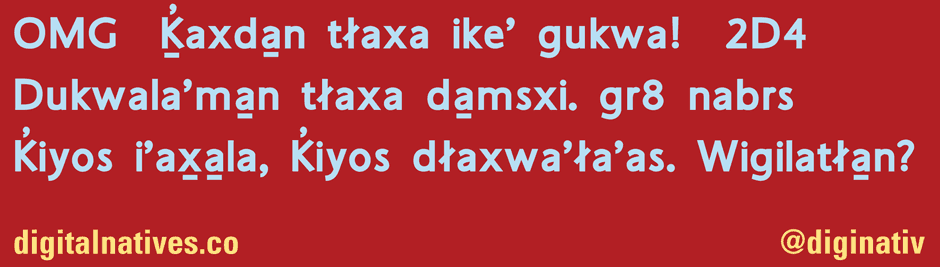

In 2009, the Skwxwú7mesh Nation installed an electronic advertising billboard at Burrard Street Bridge in Vancouver, its 18-metre footing placed on the Skwxwú7mesh’s Kitsilano Indian reserve No. 6. At three by ten metres, the face of the billboard is one third larger than most illuminated signs in Vancouver and (like many others) is larger than the 21.5 square metres permitted by Vancouver bylaws. These regulations do not apply to development on Indian reserve lands. The digital signs, facing north and south, flash a static advertisement every ten seconds. For pedestrians, cyclists and motorists entering and departing downtown, the signs are hard to miss. This occupation of visual space has been the subject of considerable public controversy.

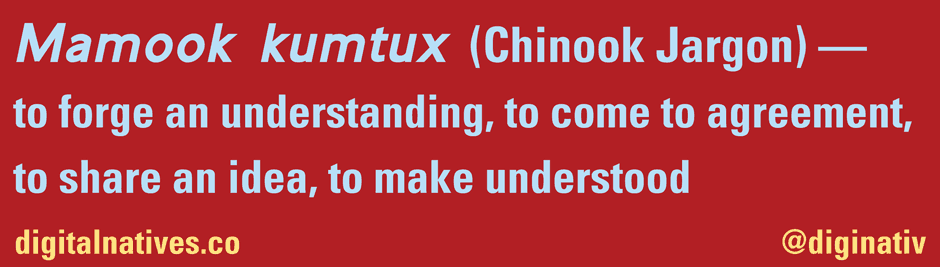

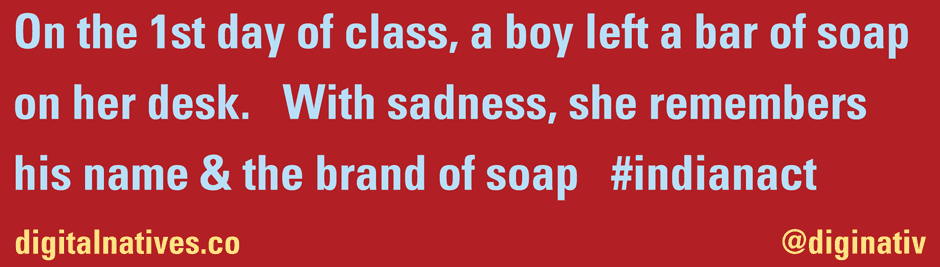

The lands on which the billboard stands is also a site of controversy – reflecting a history of colonialism, dispossession, and assertions of Aboriginal territory from a number of First Nations, including the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh (Burrard). This place has a rich Indigenous history that historical narratives emphasizing the development of the City of Vancouver have minimized and, at times, erased.

False Creek was the site of an ancient village known in the Musqueam language, hən’q’emin’əm’, as sən’a?qw and in Skwxwú7mesh as Sen’ákw. In 1869, the colonial government set aside a small Indian reserve at the creek mouth, and in 1877, the government allotted the reserve to the Squamish alone. Over time these lands were fragmented and alienated from a much larger Indigenous landscape. The next 100 years saw the reserve intersected with railway lines, the Burrard Street bridge, and various leases. By 1965, the entire reserve had been sold off. In 2002, the Squamish Nation regained a small section of the earlier reserve: today’s Kitsilano Indian reserve No. 6.

The following chronology and maps provide an approximation of some of the changes to the Kitsilano reserve, illustrating its transformation from a Coast Salish village to an industrial and urban space.

Timeline:

August Jack Khahtsalano, his wife Swanamia (Marrian) and a child in a dugout canoe, circa 1907. Vancouver City Archives, item CVA 1376-203.

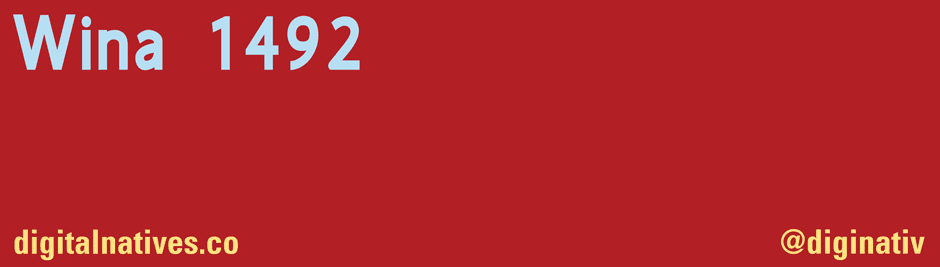

1858 The Fraser River gold rush begins and the British Columbia Act proclaims the mainland the Colony of British Columbia. Governor James Douglas sets aside Indian reserves on the Lower Fraser, some of which comprise 9,000 acres.

1864 Joseph Trutch becomes Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, and drastically reduces the size of Indian reserves previously established in the colony to approximately 10 acres per family.

1869 In response to a petition by Snatt and others, Joseph Trutch sets apart a small Indian reserve of 37 acres at False Creek for the use of the Aboriginal peoples living there. The village contains houses, a longhouse (located on land underneath the Burrard Street Bridge), a cemetery, and orchards. The hən’q’emin’əm’- and Skwxwú7mesh-speaking peoples of the time fish on what later becomes Granville Island and take advantage of wage labour opportunities at the Burrard Inlet sawmills. The village was known as the False Creek Indian Reserve, and later the Kitsilano Indian Reserve.

1871 British Columbia joins the Canadian Confederation. “Indians” and “lands reserved for Indians” come under the jurisdiction of the federal government.

1876-1877 In 1876, the federal and provincial governments establish the Joint Indian Reserve Commission to allot Indian reserves throughout British Columbia. The commissioners visit False Creek and confirm and expand the reserve there to 80 acres by running a line north to English Bay. The commission sets aside the reserve for the “Skwawmish Tribe.” It is one of 28 Indian reserves allotted to the Squamish in Howe Sound and Burrard Inlet.

1890s The Canadian Pacific Railway builds a trestle bridge across False Creek in the 1880s. The bridge soon becomes an obstacle to navigation, as it does not swing open to allow tall ships to pass into False Creek. The Kitsilano trestle is part of the electric interurban streetcar route operated by the B.C. Electric Railway, and it is demolished in 1982.

1900s In 1901, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company acquires the Vancouver and Lulu Island Railway and obtains a seven-acre right-of-way on the reserve. By 1905, the CPR has leased the railway to the B.C. Electric Railway, which operates the city’s streetcars.

1904 In 1904, The False Creek Indians surrender for the purpose of leasing 11.16 acres of the reserve to the Harrison River Mills Timber and Trading Company for a period of 50 years. In the terms of the agreement, Chief George and other False Creek residents stipulate that the company erect a fence around the graveyard, provide materials and wages for the construction of new houses, compensate for fruit trees removed, and pay a yearly rental of $200. The Rat Portage Lumber Company, the operator on the site, hires individuals from the reserve to work in the mill.

1913 Representatives of the provincial government enter the reserve and coerce the residents into selling the land. They pay each male head of family $11,250 to evacuate. Many of the residents and their property are placed on a barge and transported to the Squamish reserves in Howe Sound. Others return to homes at Musqueam and Coquitlam. These negotiations do not follow the provisions of the Indian Act, which regulates the surrender of Indian reserve lands. The land remains an Indian reserve under the management of the Department of Indian Affairs. However, most of the reserve’s residents never return. In 1928, the federal government agrees to pay the Province $350,000 for its interest in the land.

1920s Early in the decade, the reserve lands are logged by unemployed World War I veterans. Also by this time, the False Creek channel has been dredged filling in the reserve’s foreshore and the sand bar at Granville Island.

1923 The Squamish Bands of Howe Sound and Burrard Inlet amalgamate into a single administrative entity. The Tsleil-Waututh (Burrard Nation), considered “Squamish” by the Department of Indian Affairs, does not join the amalgamated Bands.

1930s Non-Aboriginal “squatters” make their home on the shoreline and waters of False Creek.

Squatters’ houseboats nestled between the CPR trestle bridge and the Burrard Street in the 1930s. Vancouver Public Library, no. 13177.

One of the last squatter’s shacks near the Burrard Bridge on False Creek, Nov. 13, 1934. Vancouver City Archives, item Wat P128.

1930 In September, the City of Vancouver applies for a right-of-way on the Kitsilano reserve for a bridge, under provisions of the Indian Act that allowed for the expropriation of reserve lands for public works. The right-of-way of approximately 6.2 acres bisects the reserve to link downtown Vancouver with growing Kitsilano. The steel truss bridge, embellished with concrete towers, art deco details, and the busts of Captain George Vancouver and Admiral Sir Harry Burrard-Neale, opens on Dominion Day, the first of July 1932. The architect is George Lister Thornton Sharp; the engineer John R. Grant.

People enjoying the beach on the Kitsilano Indian Reserve by the new Burrard Street Bridge, 1932. Vancouver City Archives, item Park N9.6.

1934 In August, under section 48 of the Indian Act, the Department of National Defence applies for lands on the reserve to build the Seaforth Highlander Armoury. The department obtains four acres for an annual fee of $7,500. That year, the Department of Indian Affairs also grants the Ruddy-Ducker Company a permit to erect painted, printed and/or illuminated advertising signs on two strips of the reserve visible to people crossing the Burrard Street bridge.

View looking south on the Burrard Street Bridge, showing billboard advertising for Turret Cigarettes and Henry Hudson School, 1932. Vancouver City Archives, item CVA 20-98.

1942 The Department of Indian Affairs leases 41.74 acres of reserve lands north of the Burrard Bridge and the CPR right-of-way to the Department of Defence for the duration of WWII and three years thereafter. The Royal Canadian Air Force uses the land as an equipment depot. Chief Moses Joseph, Chief Mathias Joe, and the Squamish Council agree to the lease for an annual rent of $5000, donating, on behalf of the Squamish, $2000 of the first year’s rent to the war effort. The “squatters” on the waterfront are evicted.

1946-1965 In April 1946, the Department of Indian Affairs takes from the Squamish Council a surrender under the Indian Act for the Kitsilano reserve. The surrender stipulates that the reserve be sold for at least $600,000, from which the province is to be paid $350,000 (as agreed in 1928) for its interest in the land. Over the following years, various parcels are sold to a number of parties, including the Department of Defence, the Department of Reconstructions and Supply, the Department of Public Works, and Girody Sawmills. By 1965, the entire reserve has been sold off.

1966 In October, the federal government turns over the RCA site to the Vancouver Park Board, which opens Vanier Park on May 30, 1967. The H.R. MacMillan Space Centre and the Vancouver Museum complex opens in 1968.

1977-2002 In 1977, the Squamish Nation initiates legal action to reclaim parts of the reserve that have been sold. Following years in the courts, which also hears counterclaims by the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations to interests in the reserve, in 2002 the Skwxwú7mesh secure control over a misshapen fraction (the railway rights-of-way) of the earlier, larger reserve.

2009 The Skwxwú7mesh Nation signs a 30-year contract with Astral Media Outdoor to manage the electronic billboard.