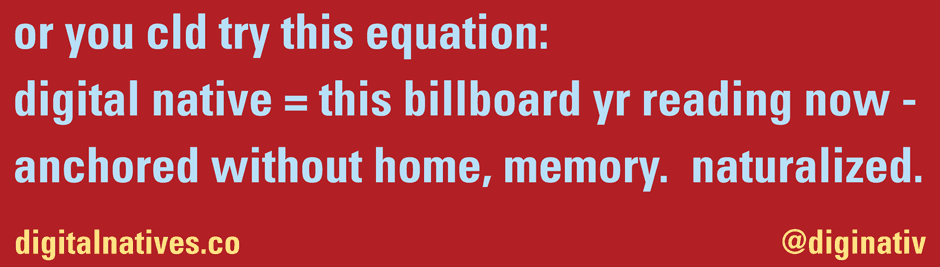

There’s really no way I can think of the teaching or the research I do as out-reach or as community-based – as much as I would like it to be and as much as it pains me that my work doesn’t do this. Instead, I see my role as a professor of digital media and digital poetry as one that involves helping my students become the digital natives they’re poised to be – they may have grown up with digital technology in a way that I didn’t, they may have had facebook pages since they were in junior high school, but I’m not convinced this means they understand how these networks (of power as much as technology) work on and through them. (And in this sense, I sometimes think that “digital native” as it’s unthinkingly used in digital media criticism is a handy term to relinquish any responsibility to learn digital literacy skills.)

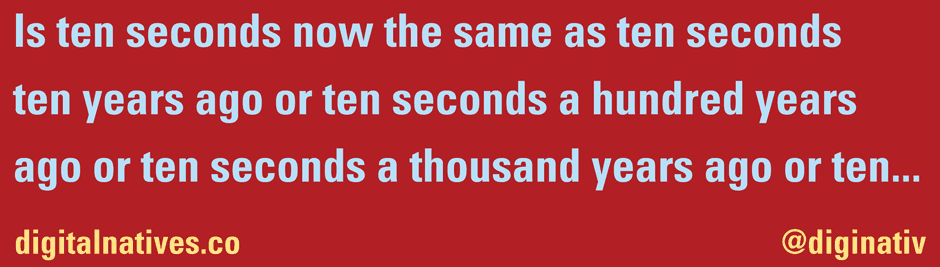

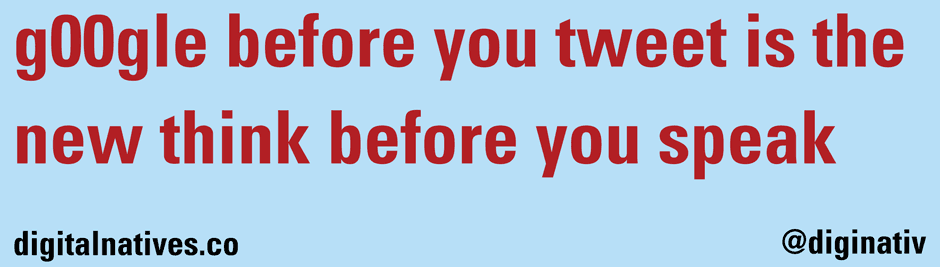

One of the ways I try to begin this process of uncovering networks of power (as I’m calling it here, anyways) is to look at how particular media structure what can be thought, written, expressed. What kind of writing do you produce when you handwrite? Have you ever written anything on a typewriter? How does this experience compare with using a word processor? What happens to our conversation in class when we switch to twitter? to a chat-room?

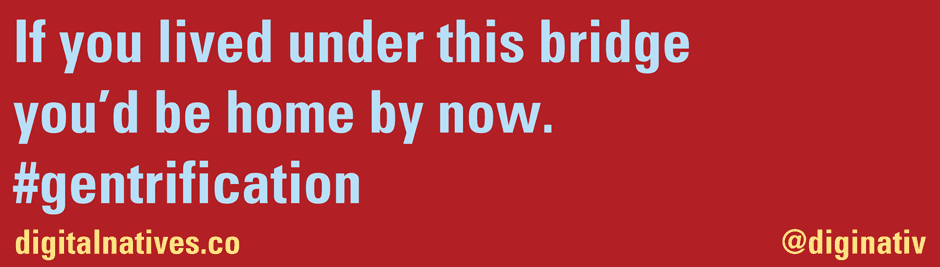

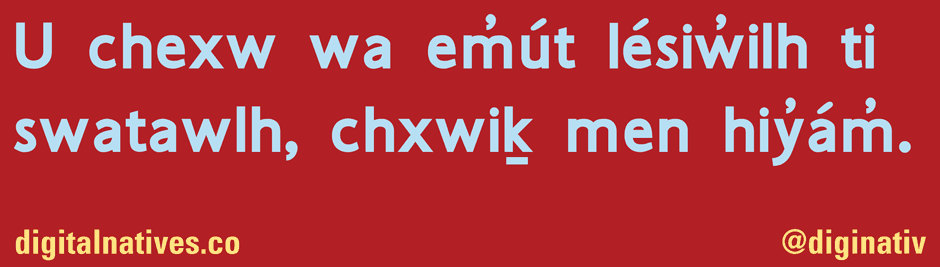

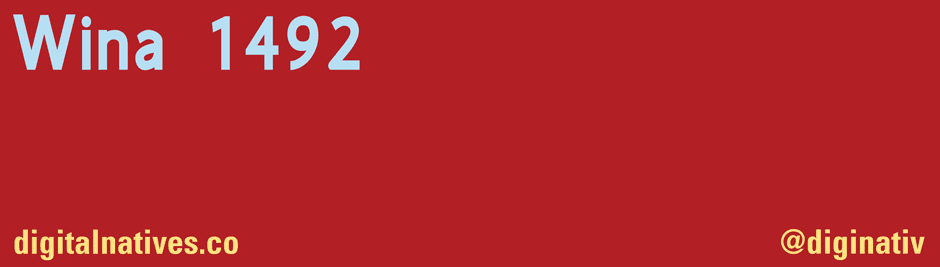

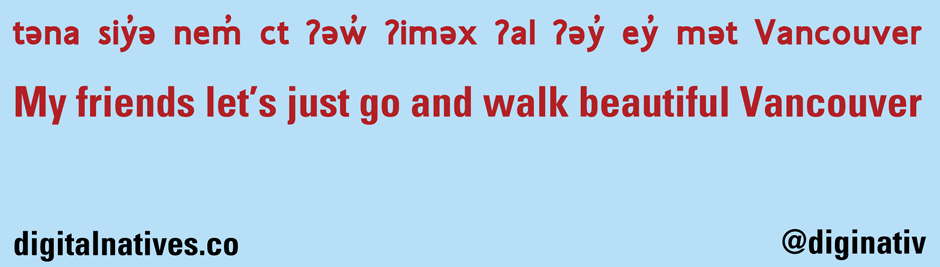

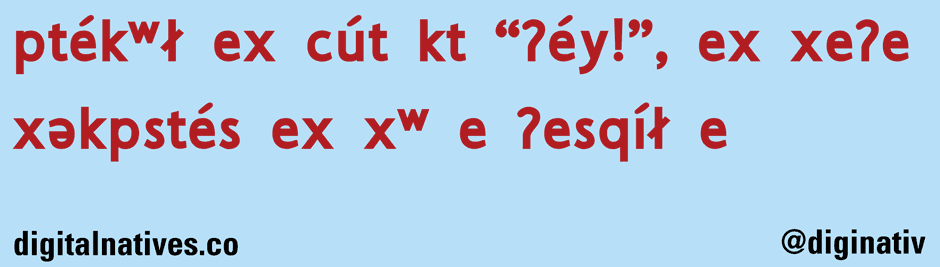

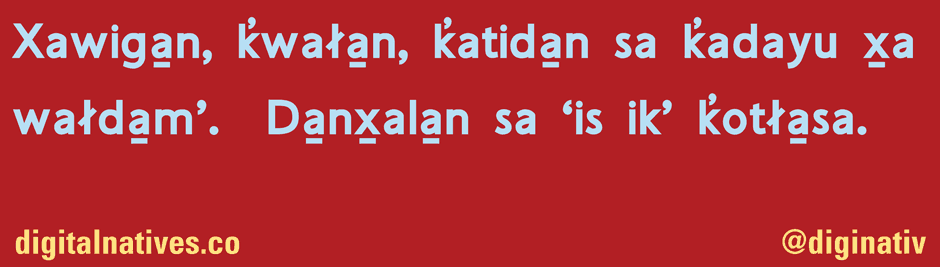

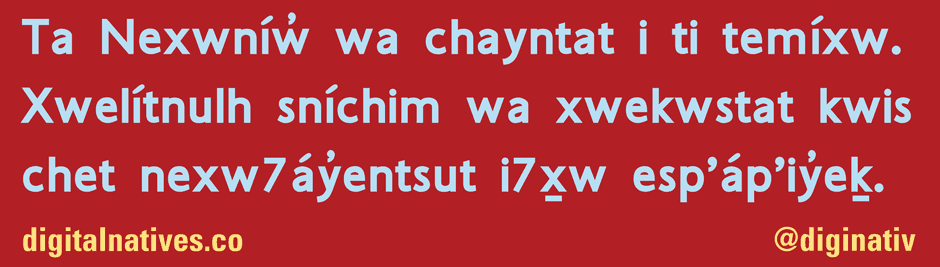

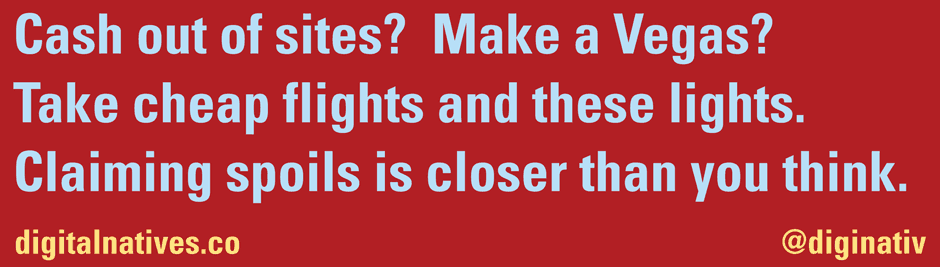

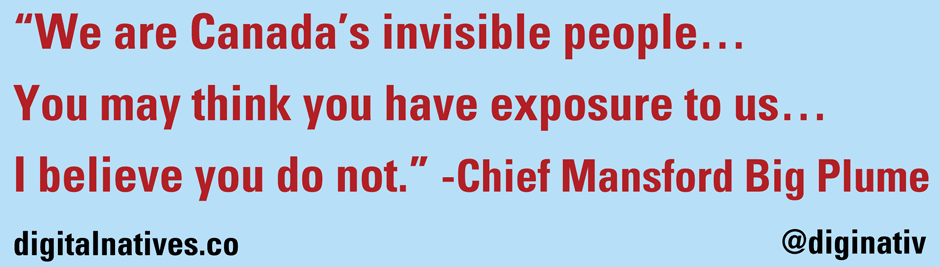

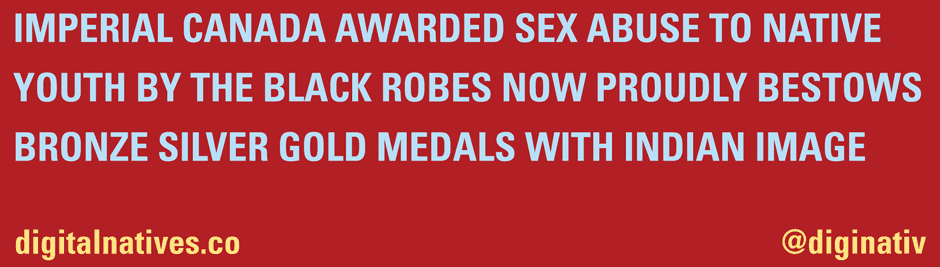

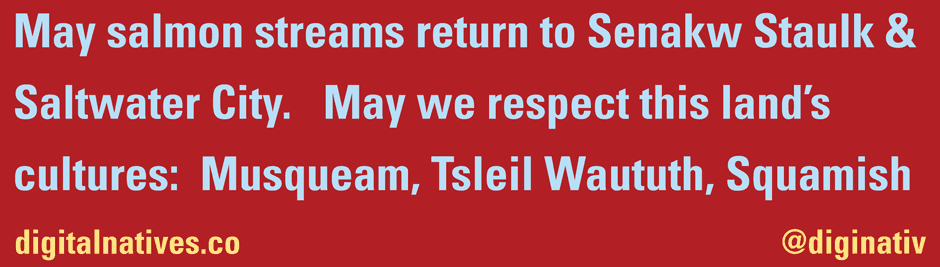

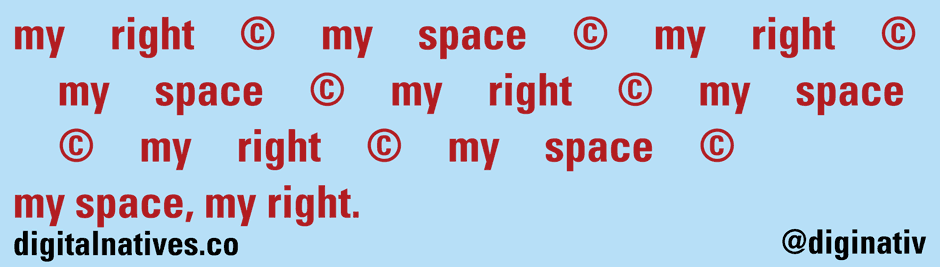

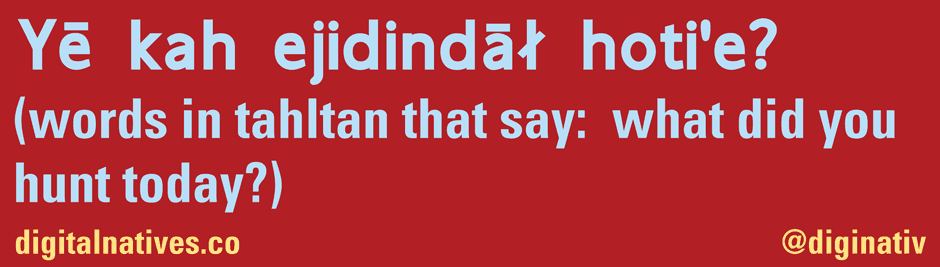

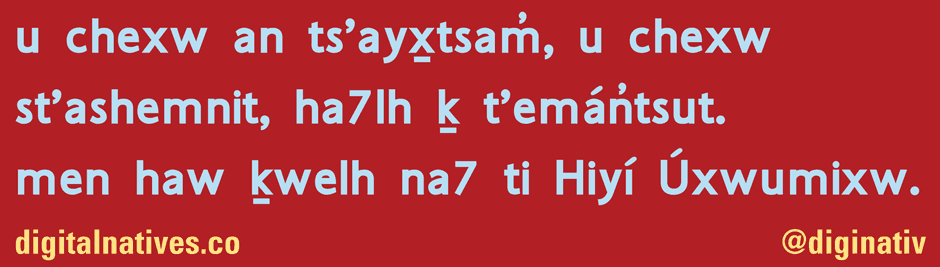

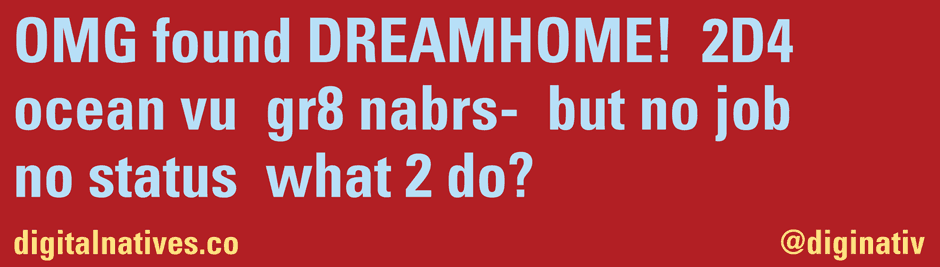

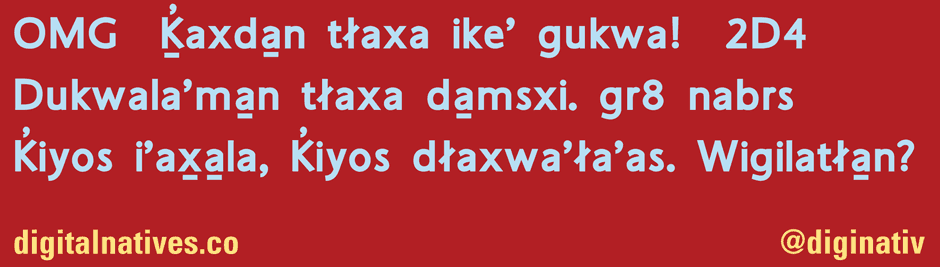

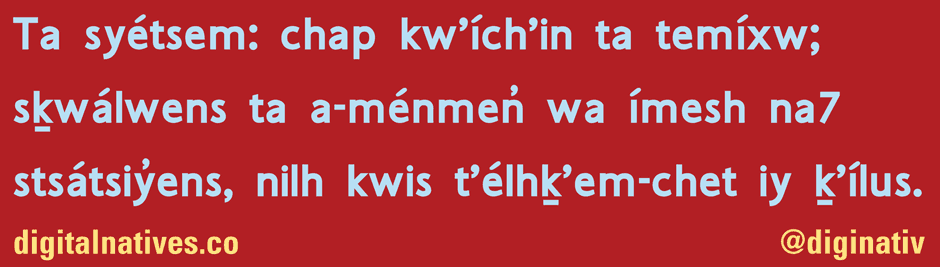

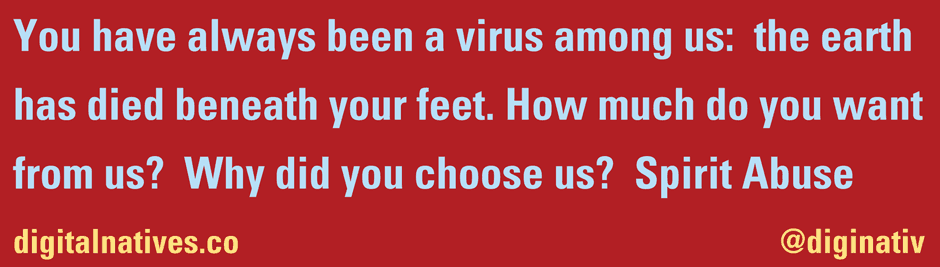

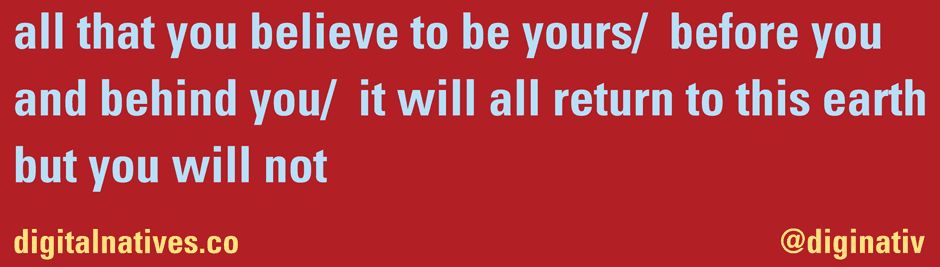

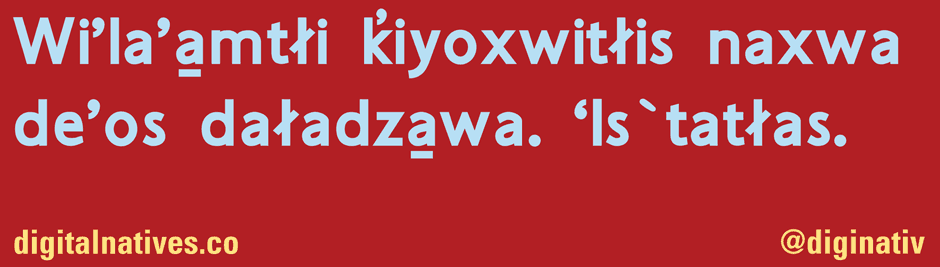

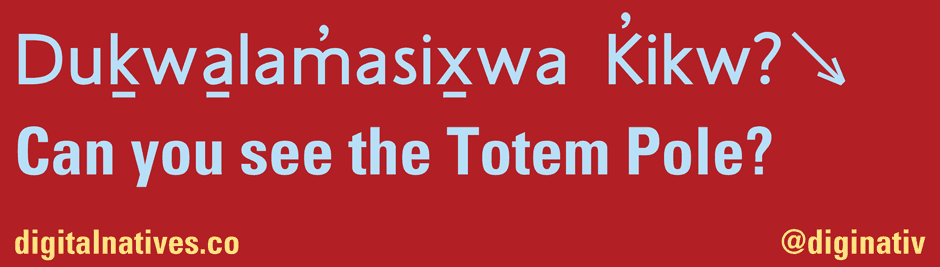

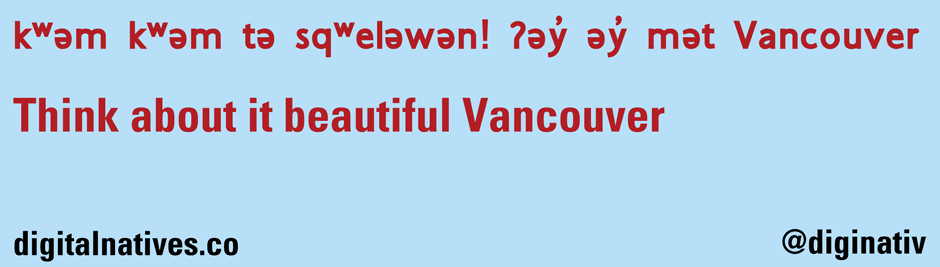

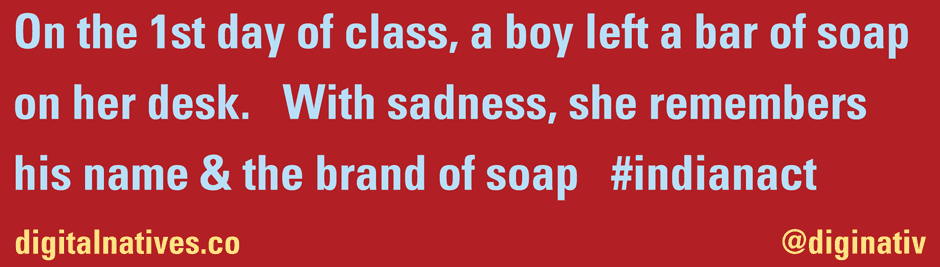

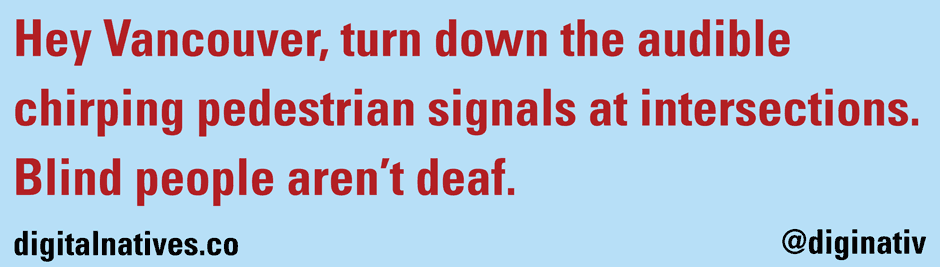

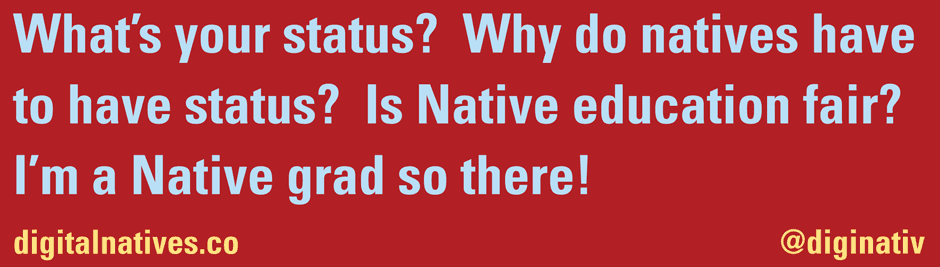

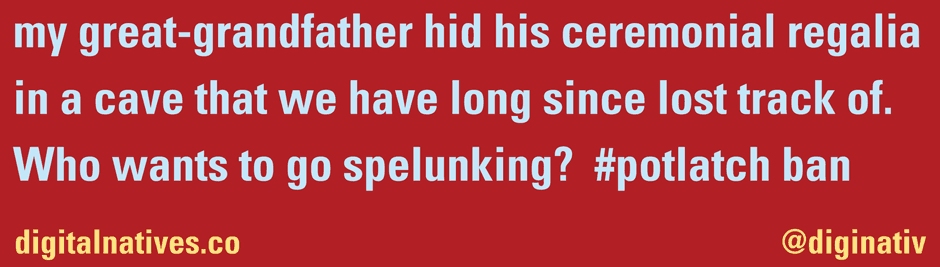

Along those same lines, then, I’m curious about what happens when tweets are translated into the medium of a billboard. They’re both (sometimes excrutiatingly) public, screen-based, woven into many of our daily lives, and built for broadcasting. But the billboard, the one overlooking Burrard Street Bridge, is also resolutely of a particular place, built up and over history. It is no small change in context to move from twitter to the billboard – the change doesn’t simply change the meaning of the Digital Natives Project. It creates the meaning – it is the meaning. This billboard in particular gives a home to the homelessness of digitally produced writing.

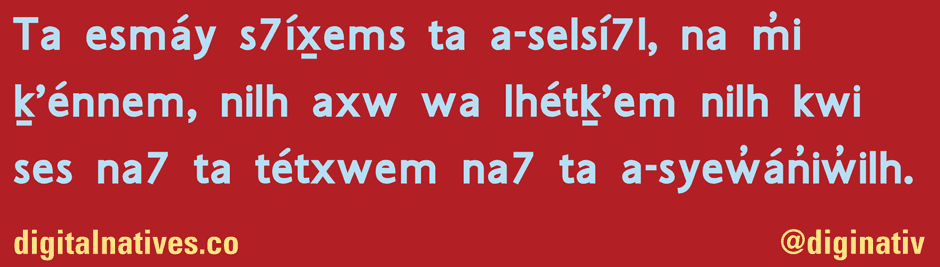

Pingback: Digital Natives, Twitter, Public Art & The Skwxwú7mesh Nation « a tale of a few cities