Many thanks to everyone who made the Digital Natives Symposium such a great event. It will give us a great deal to consider and reflect upon as we move toward producing a publication for the project. Since so many of our contributors and our 300+ followers on Twitter are scattered around the world, I am posting this (very) brief summary of the proceedings as well as responses that arose during the discussion that followed.

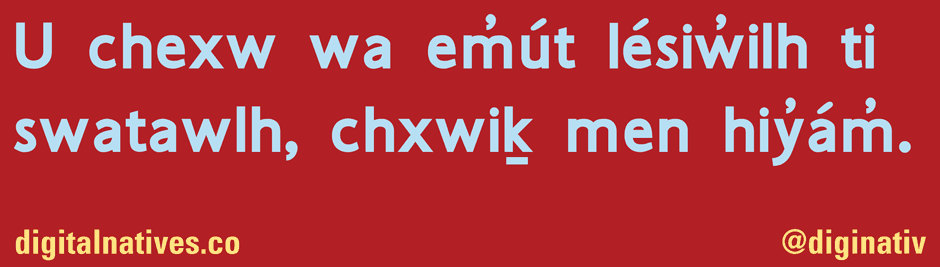

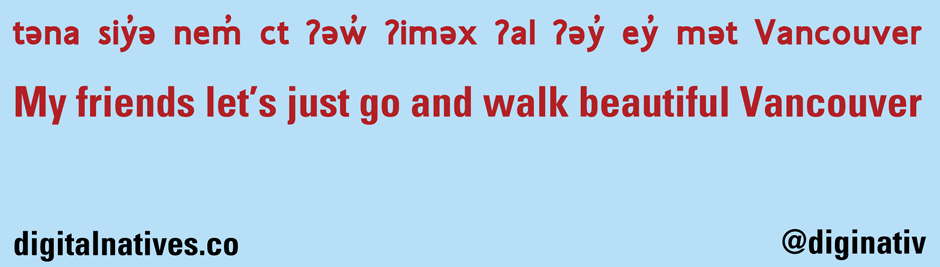

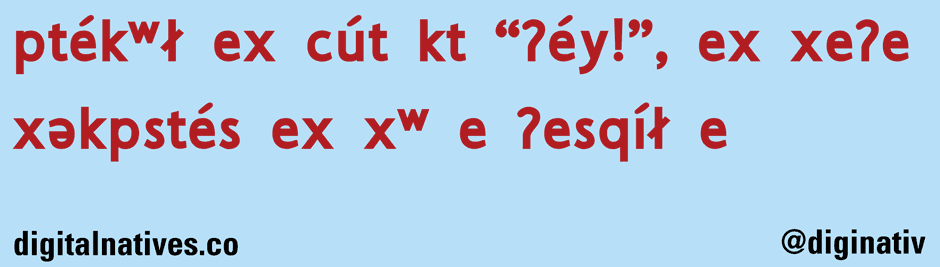

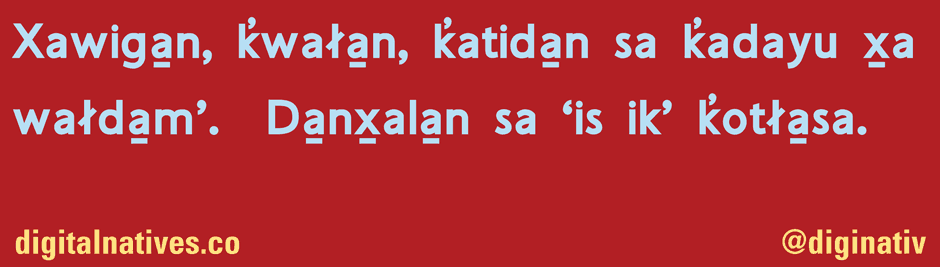

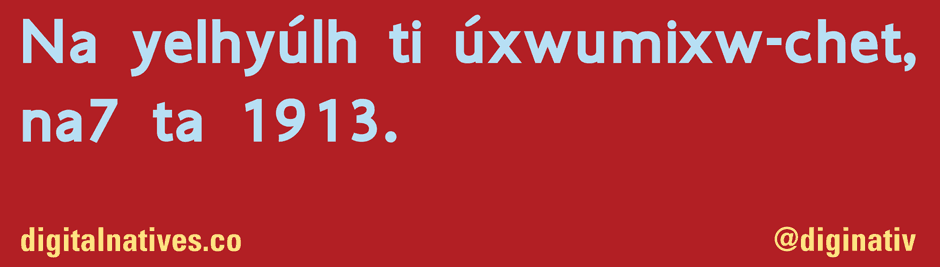

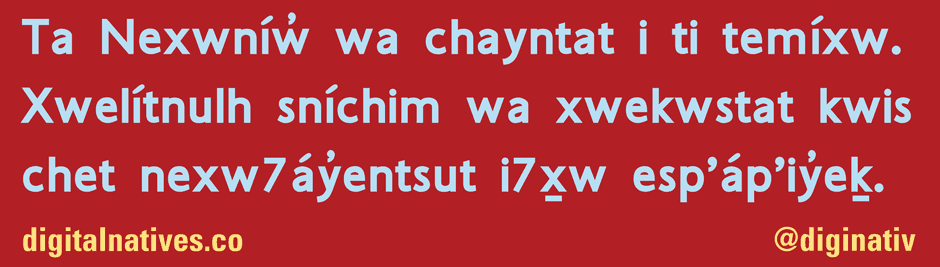

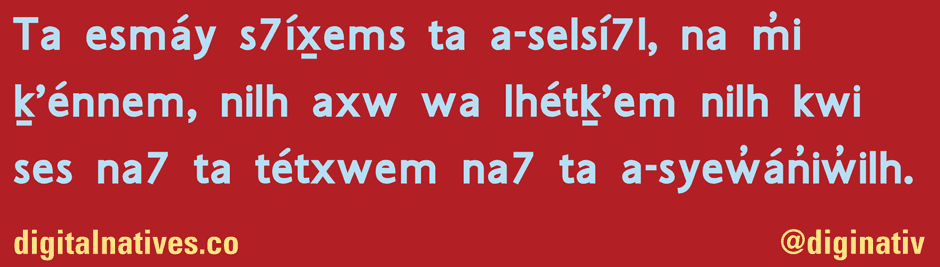

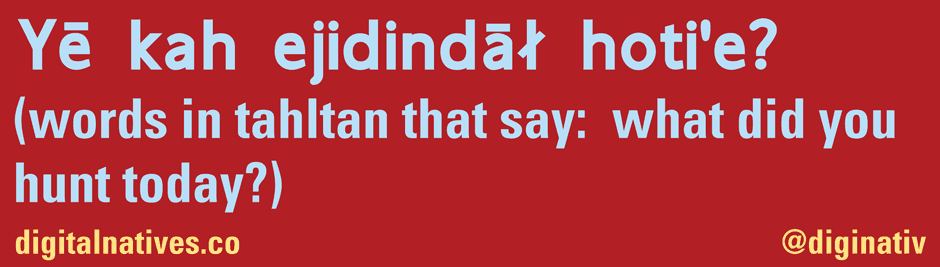

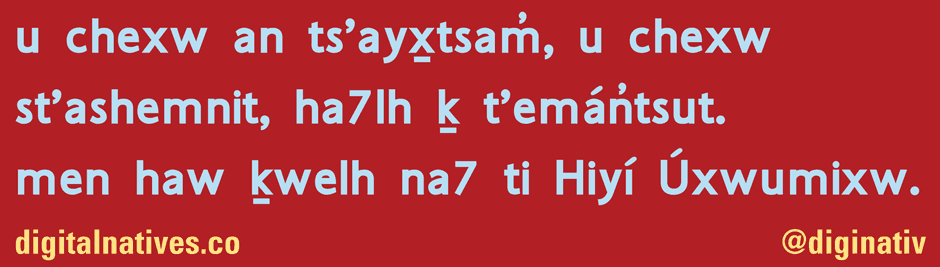

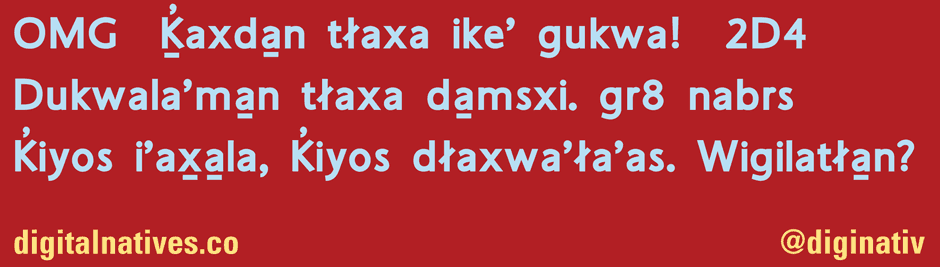

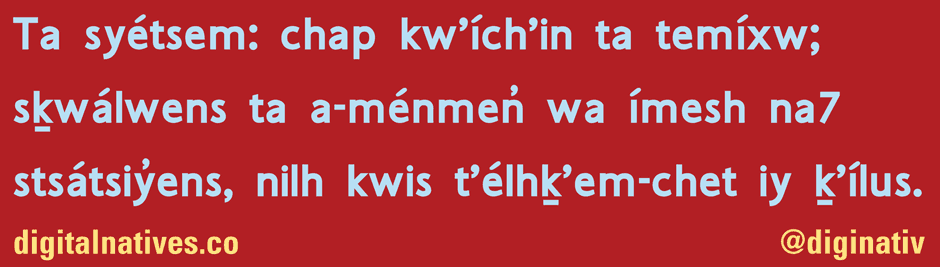

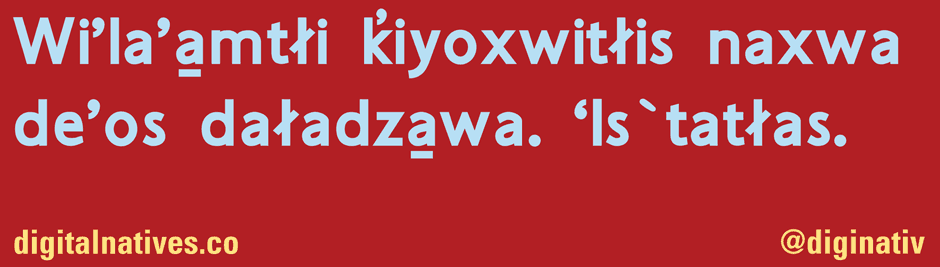

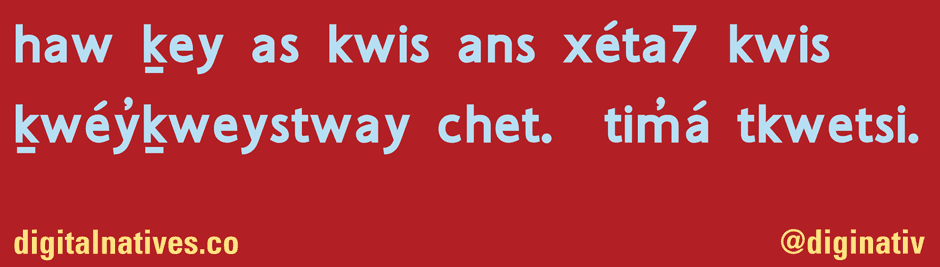

Many thanks to Henry Charles, Storyteller in Residence at the Vancouver Public Library, for his gracious welcome to the participants. Henry’s translation of messages to hǝn’q’ǝmin’ǝm’/Musqueam, as well as his own bilingual messages for the billboard are much appreciated.

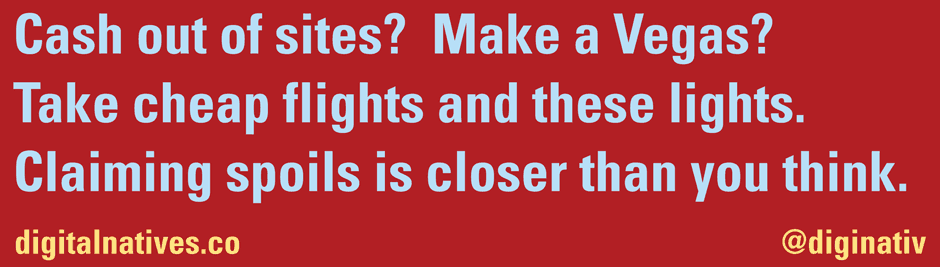

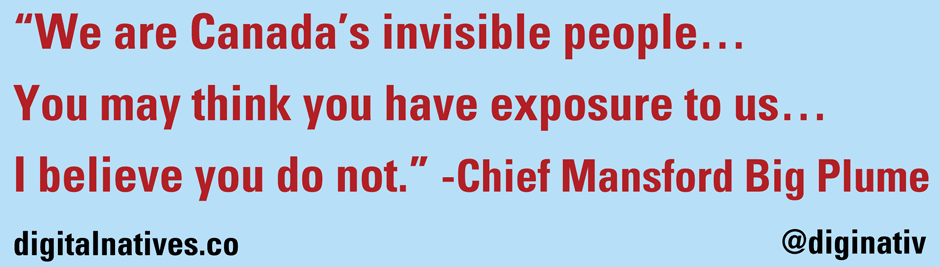

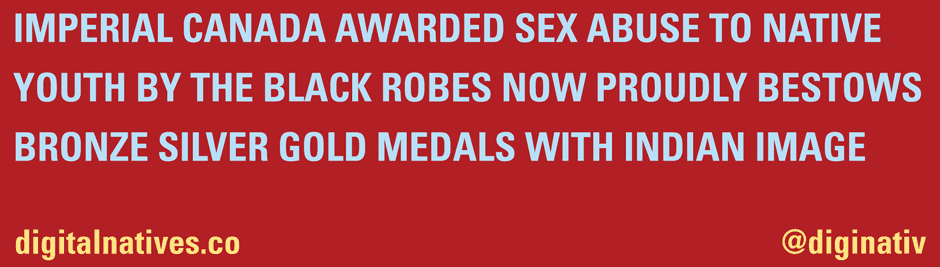

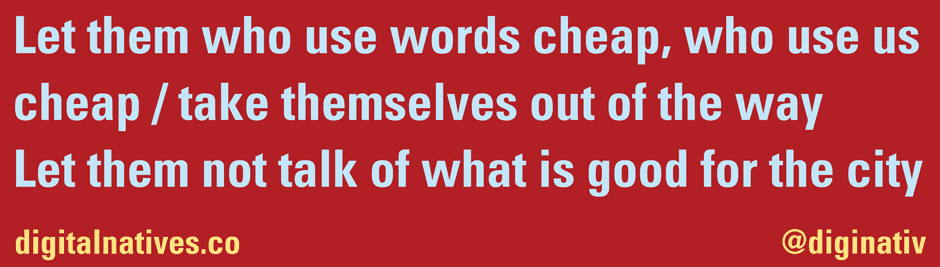

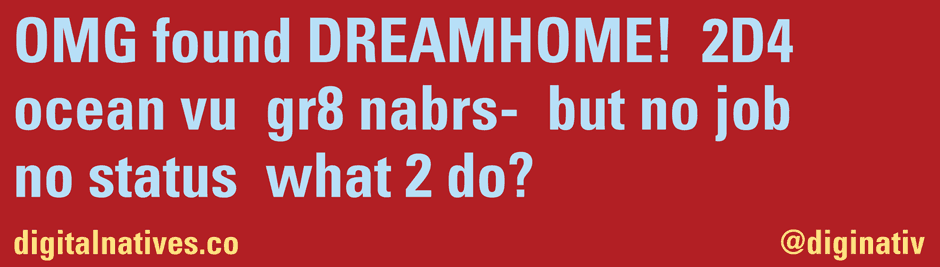

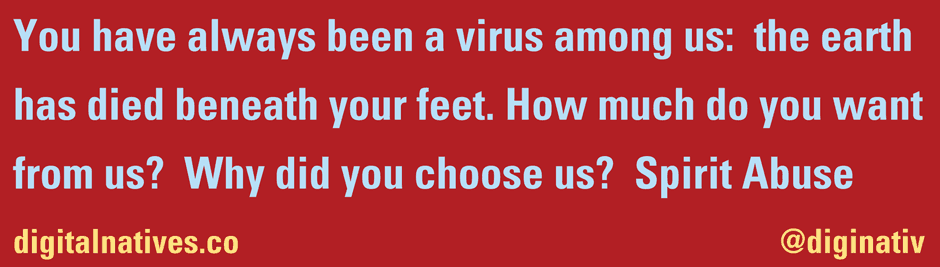

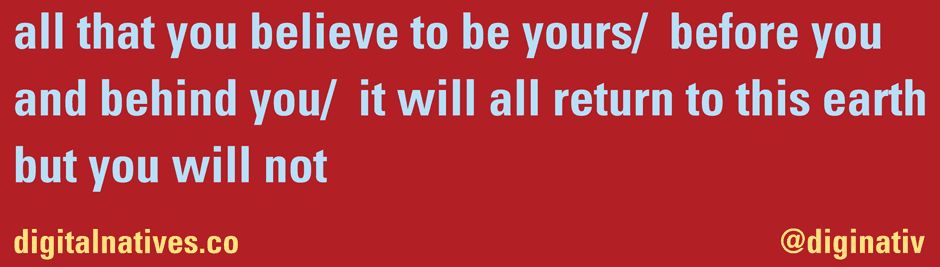

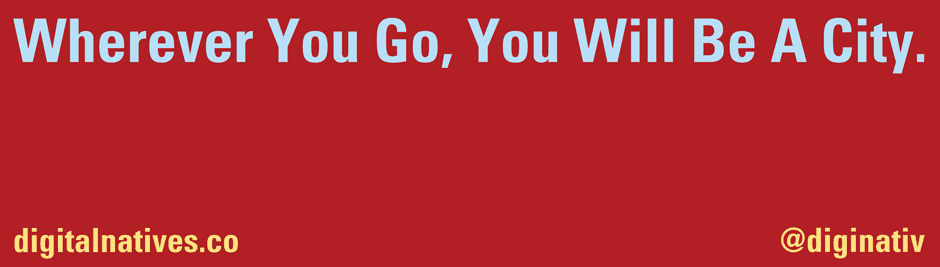

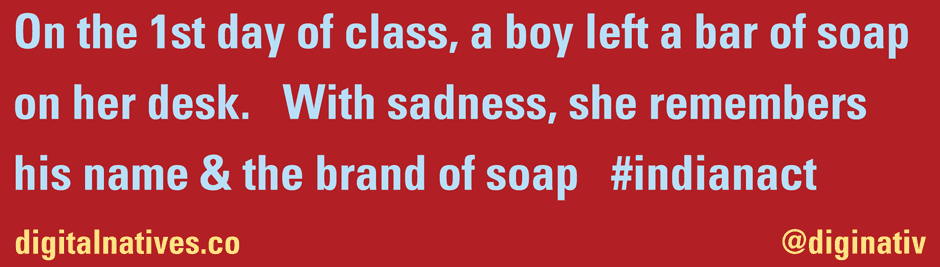

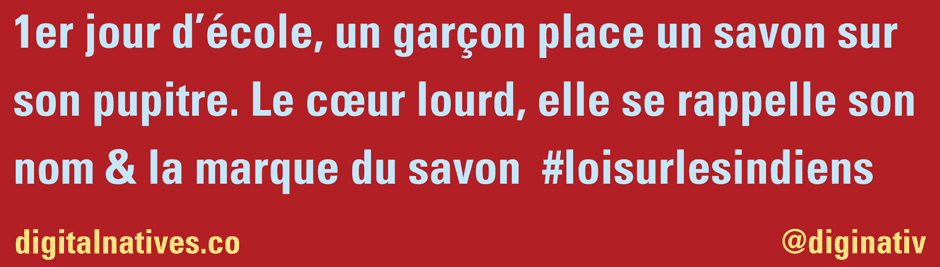

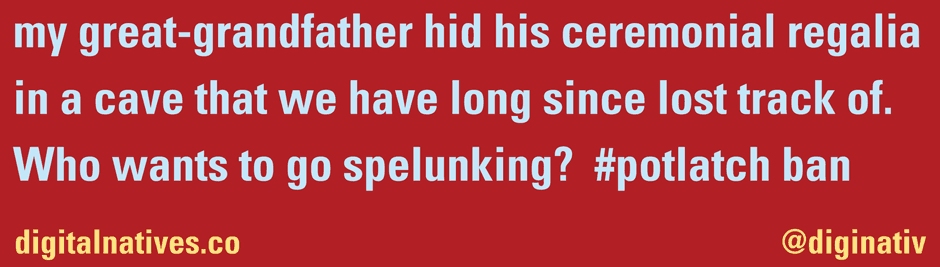

Our first roundtable presenters were Sonny Assu, Edgar Heap of Birds, and Jeff Derksen. Sonny spoke about how his messages were excerpts of conversations with his grandmother about family history. Her memories of residential school, his grandfather’s decision to hide ceremonial regalia in a cave that cannot now be located were two among many tweets that he composed. He talked about his creation of #potlatch ban and #indianact hashtags as a hopeful gesture for twitter exchanges about these recent histories and a means to retrieve and cluster them. Edgar presented his memorial work about the indentured American Indians that performed across Europe as part of the Wild West Show and the many who died there, and whose remains have yet to be re-patriated. His message for Digital Natives that was censored by Astral also speaks to the need to first acknowledge and honour those who came before. Jeff placed the project within bodies of thought around ‘the right to the city’, and how city space is for living and is diminished the more it is commodified. He discussed Duncan Campbell Scott, the 19th century poet noted for composing sentimental poems about indians, while at the same time working to frame the language of the Indian Act.

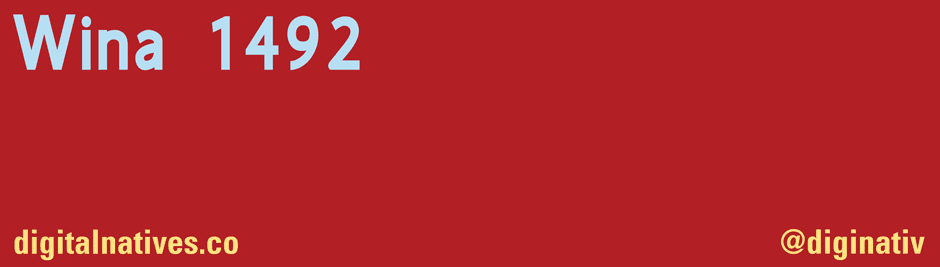

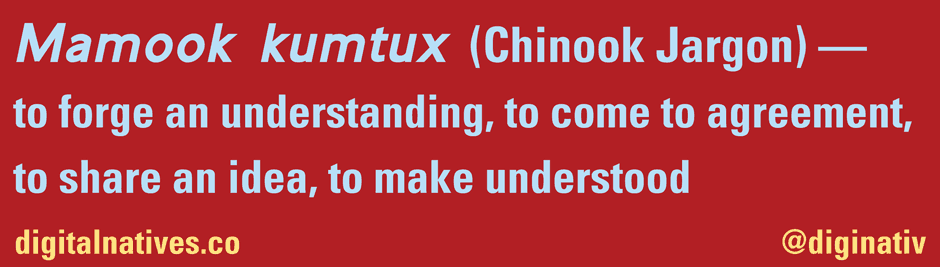

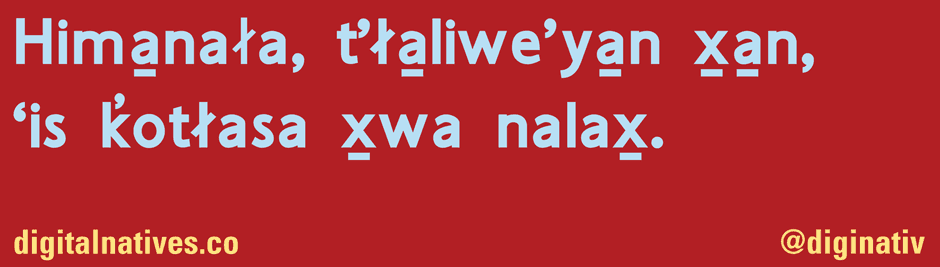

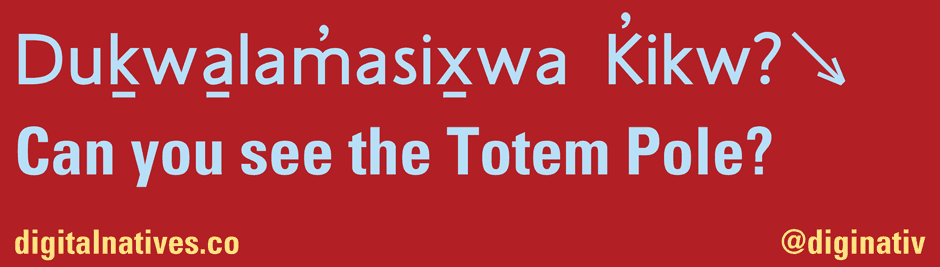

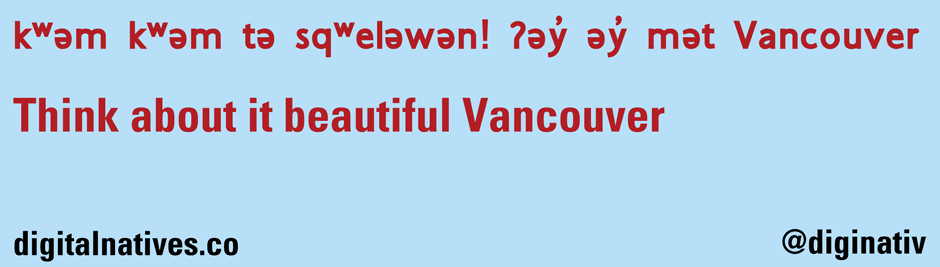

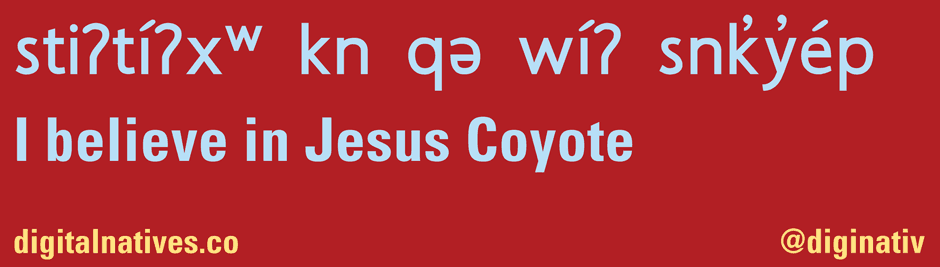

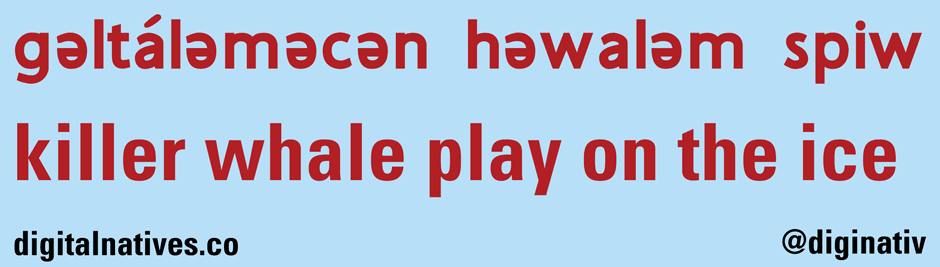

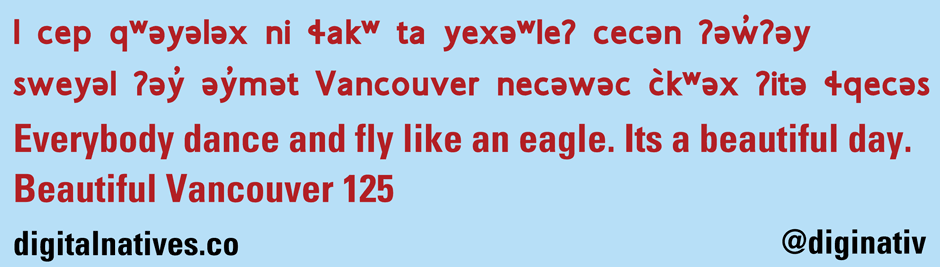

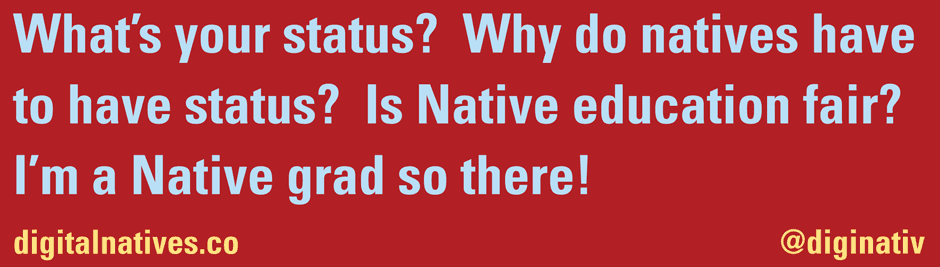

The second roundtable looked at the project from the perspectives of public space, digital technologies and translation. Annabel Vaughn commented on Digital Natives in relation to city planning’s fixation on ‘view corridors’, the symbolic impact of seeing First Nations languages in the city’s visual space, and the overlooked fact that, in making buildings, developers also create the space between them, the space of the public. She commented on how, paradoxically, the project carried a tone of intimacy between the contributors and the followers. Phillip Djwa spoke about the challenges of digital access for rural First Nations, and the finely grained generational differences when it comes to the use of digital media, and how these ideas relate to the workshops with urban aboriginal youth he conducted as part of the project. The archiving dilemmas of traditional languages and the fragility of recording technologies were discussed in relation to endangered First Nations languages. Deborah Jacobs cited a UNESCO report stating that Canadian native languages are the most endangered in the world, and addressed the complexity of the translation process undertaken by the Education, Language and Cultural Resource Management team at the Squamish Nation for the Digital Natives project. A multi-layered process, translation relies on the imaginative interpretation of intended meaning, the transliteration of sounds, concepts and histories to visual form, and an understanding that language itself has culturally specific values. This use of language is seen in the context of marking the “125th” anniversary of this place.

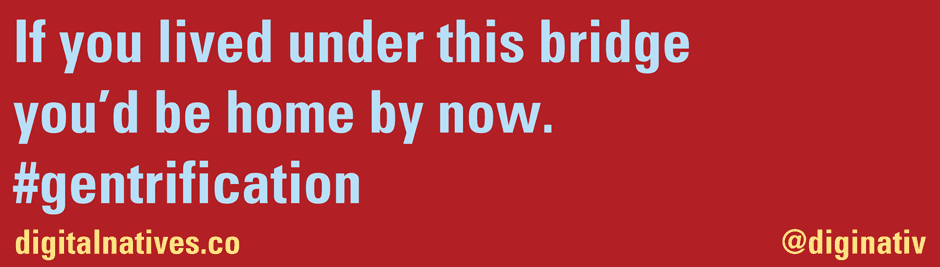

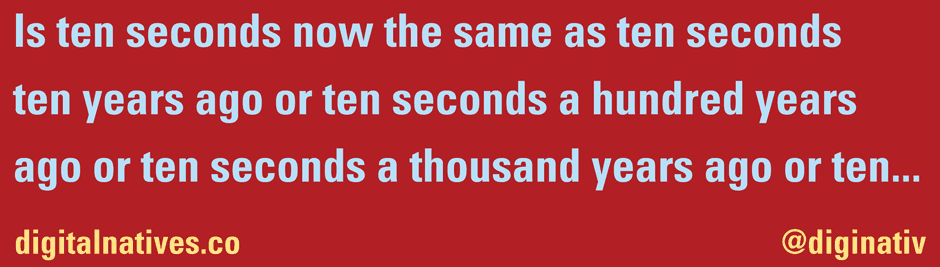

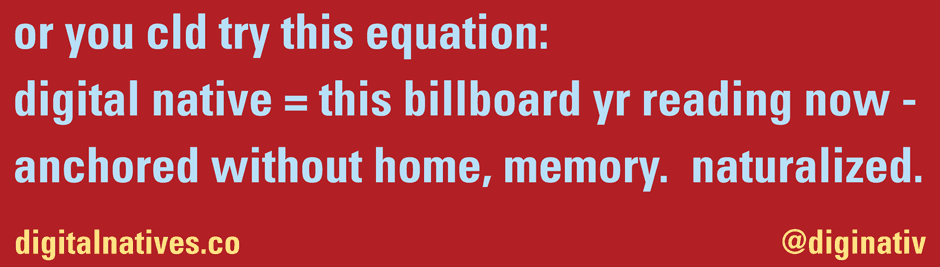

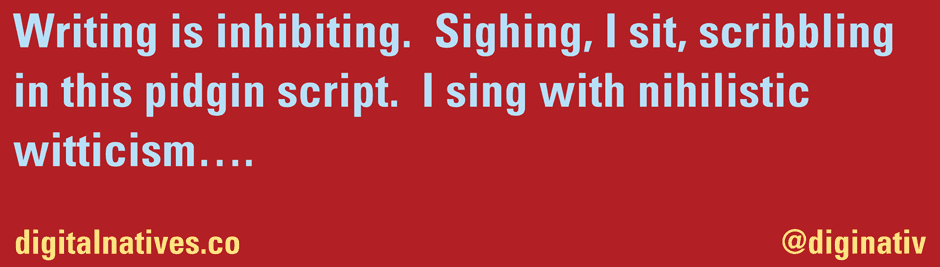

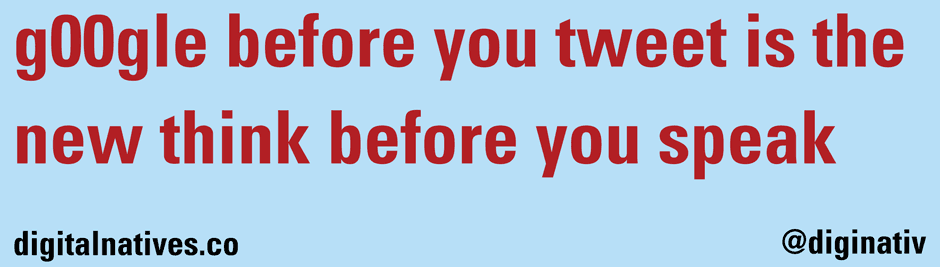

In the discussion, language was equated with sovereignty, as a way of claiming symbolic space, as treasured and also crassly commodified in an advertising context. Digital language – in the abbreviations of text messages, the hybrid forms created by the character limits of Twitter, and the incidental and intentional poetics that result, are considered alongside the work to create unicode fonts to accurately present First Nations transliterations. The speed of transmission of digital language sits next to the ten-second timing of the billboard, leaving viewers in cars straining to grasp the message, while online audiences can relax into the pace of the message roll and twitter feed, should they have the time. Bridge walkers have more opportunity to reflect, although they may resent having to pay attention to the slow pace of the ad content while waiting to focus on the next message. Operating in all these different temporal and spatial conditions simultaneously, the project’s effect is similarly multiple, and each aspect is ‘partial’ coming together only by association. As a temporary spectacle that leases a piece of the built environment, it draws together the standardized global template of the billboard with this particular location, and the particular viewpoints of the contributors and members of the public that sent us their ideas.

The symposium animators Glenn Alteen, Keeka Alexander and Kristin Kozuback drew out several themes and posed challenges to the discussion. Can public art really generate a different way of thinking? Is the symbolic presence of First Nations language in public space the most resonant, valuable part of the project? Does reaching out to involve other publics, such as aboriginal youth, have a meaningful impact? Comments about generosity – and its limits – brought the discussion to a close, as Clint recapped the days events.

I welcome all comments (and corrections!) to this summary in the field below.

Thank you to Jill Baird and the MOA staff for hosting the event, to the speakers and animators, to Barbara Cole for her introduction, and to everyone who attended.