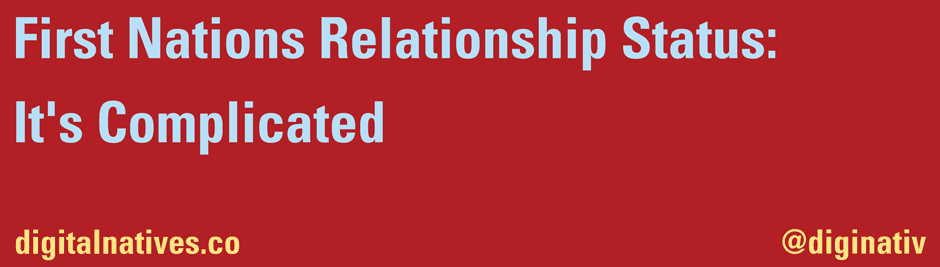

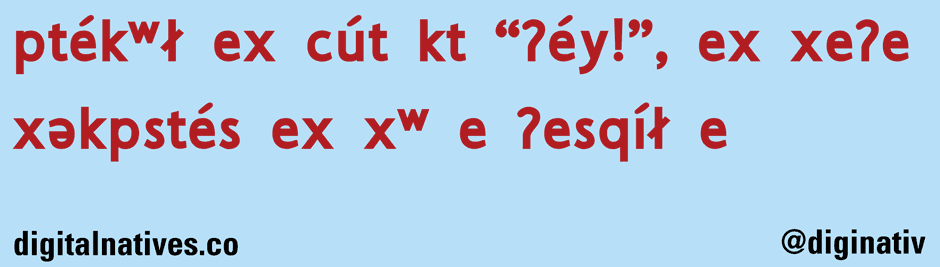

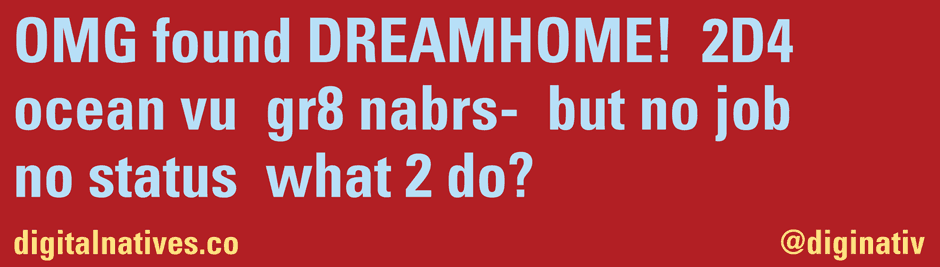

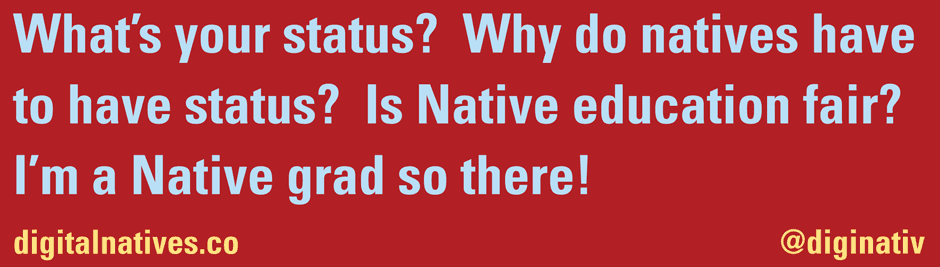

I think this Facebook inspired tweet gives my best reflection on the complicated nature of both the contested land, my own identity and the rise of social media in our contemporary world.

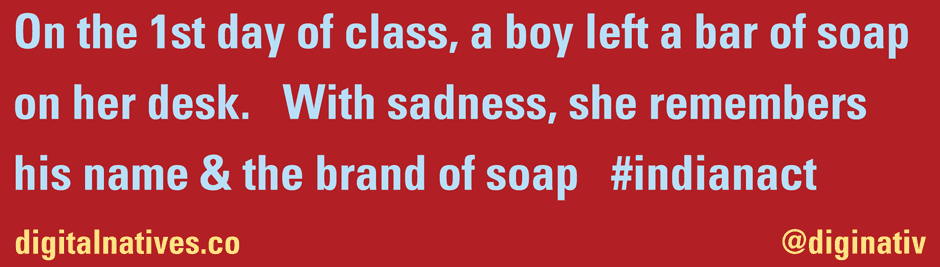

My tweet is “First Nations Relationship Status: It’s Complicated”

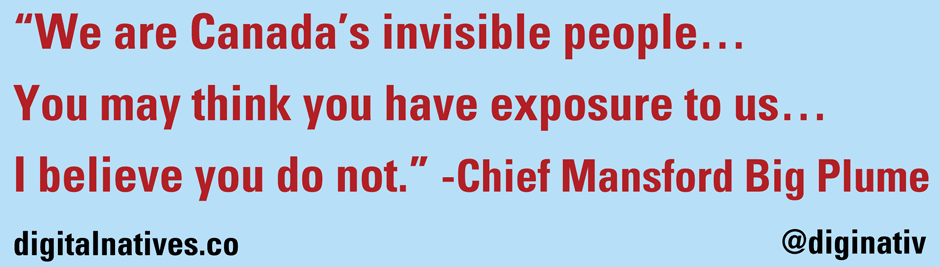

Why? Well, first, starting with the land, treaties are one of the thorniest issues when thinking about relationships with First Nations in BC. Given the glacial pace of signings, it’s going to be part of our ongoing discussions with First Nations people in BC for years to come.

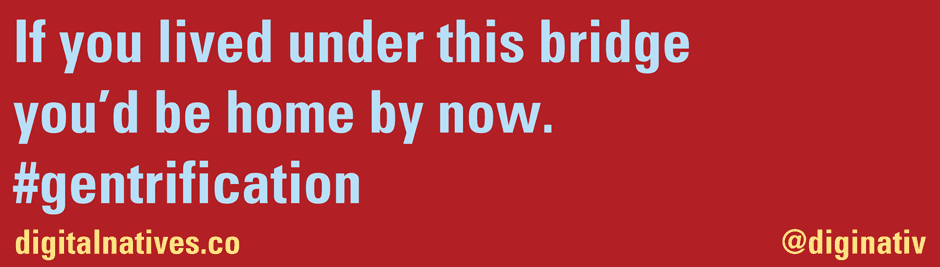

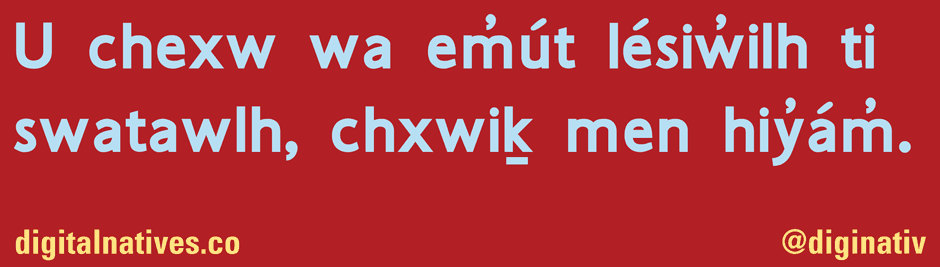

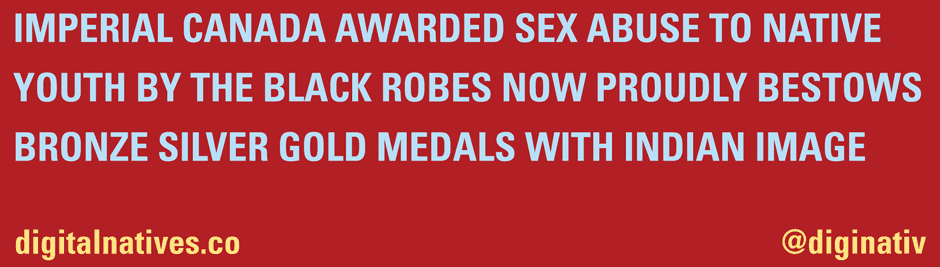

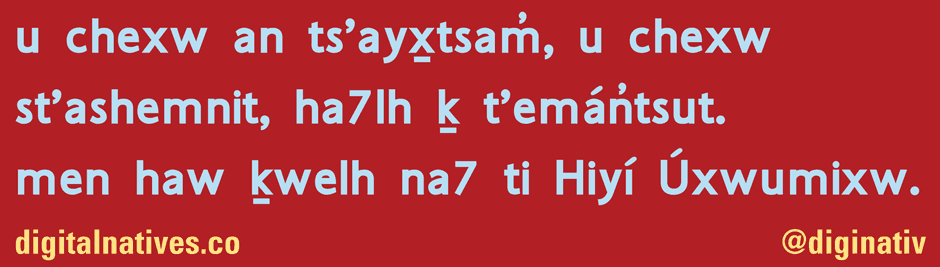

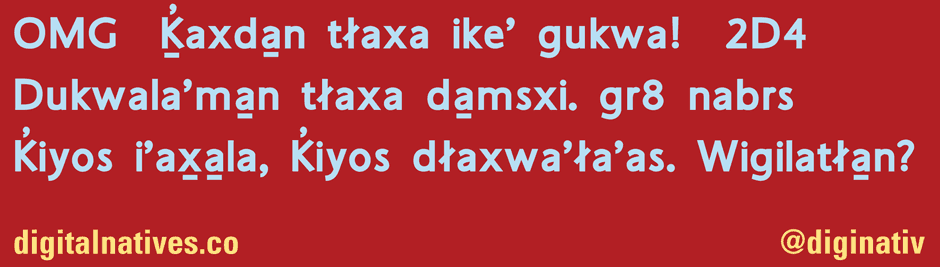

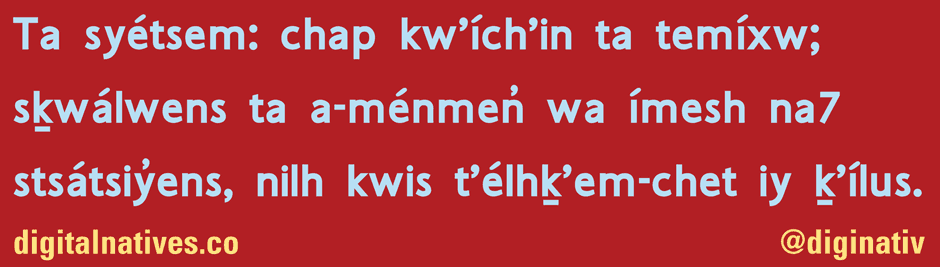

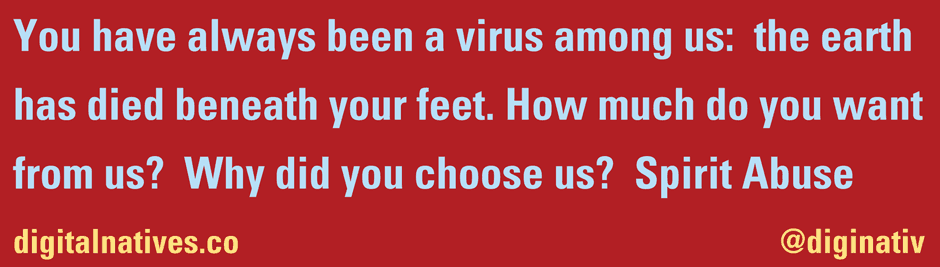

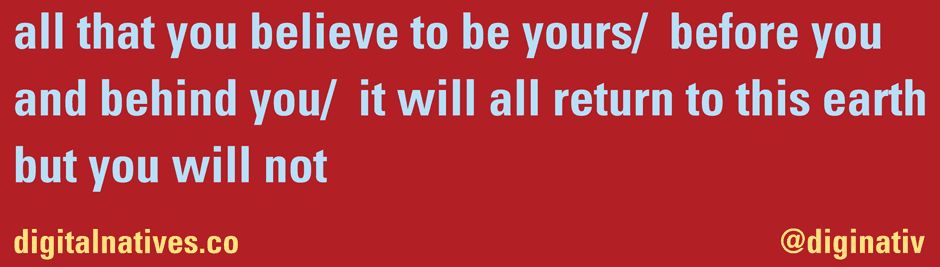

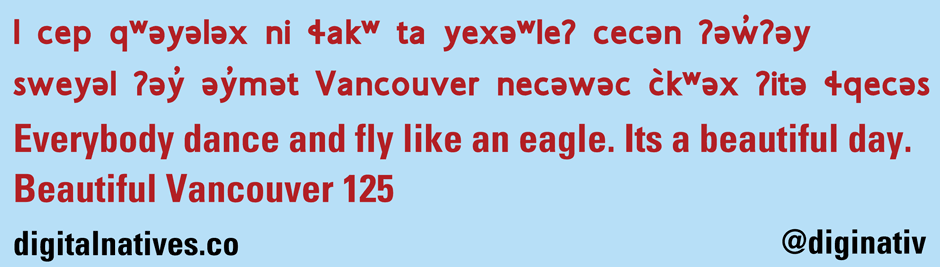

It informs us locally, in thinking about the land beneath the Burrard bridge. Reading the timelines of the efforts of Skwxwú7mesh Nation, it is really clear that it’s contested land. As the subject of debate since the 1800s, that the land has continued to be contested was never so clear as when the Skwxwú7mesh decided to put up a digital billboard in 2009 on which the Digital Natives project will be displayed.

In articles of the day, citizens complained of the eyesore; the continued encroachment of advertising and the dangers of driver distraction. But Skwxwú7mesh chief Bill Williams responded that “”It is a new and different long-term stream of funds that will be coming in to help support programs and services for our community members.[1]”

“The network will generate a $50 million revenue stream for our people over the term of the Agreement, which will be used for community projects, education, parks and recreation.” Williams adds that the advertising company Allvision “has always been respectful of our values and traditions in the work they have done for us.”[2]

Don’t you feel like the advertising is a funny confluence of conditions? Here we have our consumerist culture saying that the support of advertising is distasteful. Whether thickheaded or not, according to Wayne Hunter, head of Citizens for Responsible Outdoor Advertising, more than 10,000 Vancouverites signed a petition against the billboards[3]. Still, they proceeded.

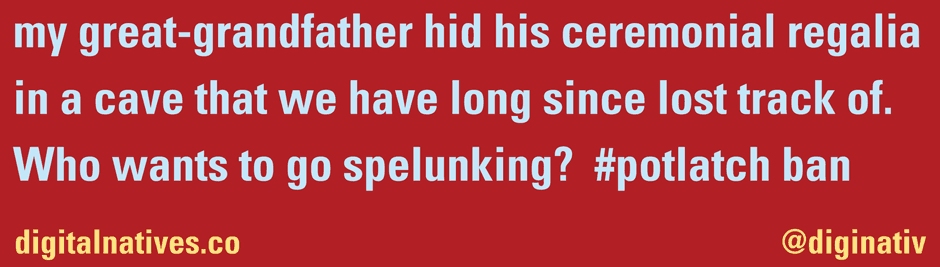

My own Native ancestry is also contested territory. My mother’s family is from Newfoundland and has been there since the 16th century. In 2004, my aunt discovered that my great-grandmother was actually not “Portuguese”, but Native. We’re not sure what nation exactly, but I assume it is not Beothuk, as they are considered extinct with the death of the famous Dewasduit in 1820, the apparently sole remaining Beothuk. So most likely it meant Mi’kmaq, who were also residents in Newfoundland. There was further evidence in the resurgence of the Conne River Mi’kmaq, who had a resemblance to my family. Well, to be honest, they were white and blonde, which was similar to my own mother. But the proof has been hard to pin down.

I was quite surprised as I had been working with native groups for about 6 years in 2004 and also careful to maintain my identity as “non-Native.” Still, it was a wonderful idea that suddenly the work I was doing was part of a larger personal narrative. But in my own mind, I still more strongly relate to being non-Native.

As a side note, in some ways, the notion of being “non” is part of my father’s makeup as well. His own historical context was as a Chinese living in Indonesia. And, as a Chinese Indonesian, discrimination as a non-Indonesian is a painful part of their history. Starting as far back as 1740, there were massacres of Chinese Indonesian’s in Batavia, which become Jakarta. And unfortunately, that violence has continued. In May 1998, the Jakarta Chinatown, called Glodok, suffered significant and tragic losses due to rioting targeting them. Over 1500 people were killed in the unrest and thousands of people lost their homes[4]. Only in 2006, was the final facets of discrimination eliminated with Chinese Indonesians being issued regular Indonesian identity cards. Previously, all Chinese Indonesians had a different category of citizenship which made it easy to identify them.

My father had decided after I was born in 1968 not to return to Indonesia because of the anti-Chinese laws that were being encouraged by Suharto’s recent rise to power. So we stayed in Canada, as examples of the emerging diversity of Vancouver and that of Canada.

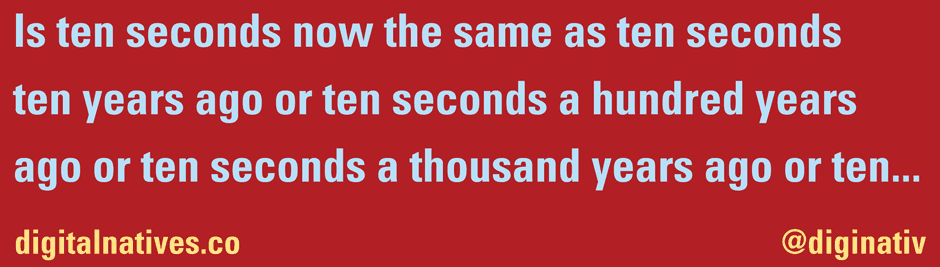

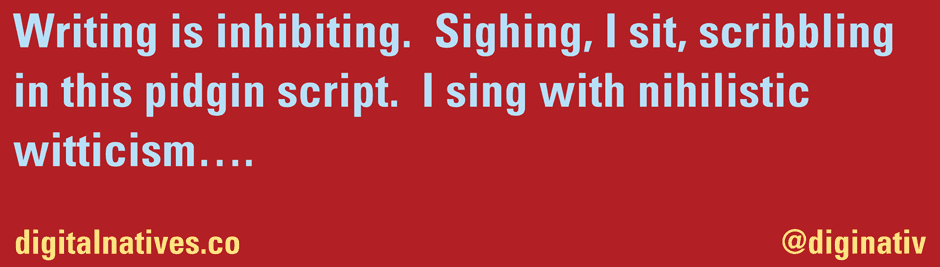

Finally, the idea of the tweet came out of Facebook. Facebook has become the new way to circumscribe our own identities. It allows us to communicate in new ways and maintain connections much greater than the so-called Dunbar’s number of 150 being the maximum number of friends we can theoretically maintain socially stable relationships.

Because of this new social entity, new ideas of relationships have emerged. One almost absurdist reduction that Facebook offers in describing your relationship is “It’s Complicated”. You have a total of eight choices to describe your relationship status on Facebook of “Single, Married, In a Relationship, Widowed, Divorced, Engaged, Separated, Open Relationship, and It’s complicated.”

According to the Urban Dictionary, the status of “It’s complicated” can refer to an “Ambiguous relationship”, one that is used to potentially show “dissatisfaction with the relationship” or a relationship that doesn’t fit into the status quo. “Holding on to something that’s about to end,” or “still hoping to work things out.” One example given was:

Gina and Chad’s engagement has been on the rocks for years but they won’t move on, they just stay together and say, “it’s complicated” whenever people ask when they’re planning to get married.

So there you have it. My hope is that this post has provided some background for the tweet. Overall, my identity and the overall complexity of the relationship with First Nations people on both the broader treaty issues and the local issues of the Burrard bridge have given me the inspiration. Thanks to the dynamic duo of Clint Burnham and Lorna Brown for allowing me the space and special props to the rest of the team of Barbara Cole, Colin Griffiths and Deanne Achong.